Year in Review 2025

Ah! The Holiday season is upon us, and that means it's time for our Year in Review! As I wrap up 2025, I want to take a moment to reflect on this year and share some of the things I've learned along the way. So grab a cup of your favorite holiday beverage, get cozy, and let's dive in (in no particular order)!

Graphics Systems: X11 and Wayland

This year I delved into the world of graphics systems, particularly WIMP (Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointer) GUIs. I learned about the history of WIMP, going all the way back to 1960s and the "Mother of All Demos", then picked up and further developed by Xerox PARC in 1970s and later discovered by Steve Jobs in 1979. Along the way, I had to learn what a Unix socket is and how it works. Here is a brief overview of what I learned.

I was often puzzled by all these terms and pieces like - window managers, display servers, display managers, desktop environments, compositors, windowing systems. In reality, they all refer to what I call a "Graphics System". Some graphics systems like X11 splits these into multiple, independent components. Others, like Wayland combines them all into one unified system. At the end of the day, the main responsibility of a graphics system is to draw pixels on the screen.

A GUI program is not a special kind of program. In fact, there are no CLI or GUI programs. There are just programs. A GUI program simply connects to the X11 or Wayland socket and starts talking to the Graphics System - "Hey, please create a window for me. It should be this size and positioned at x and y. Now show it on the screen!". The Graphics System (like X11) is simply a server, allowing clients to connect and make requests to create windows, draw graphics etc.

The Graphics System itself is also quite simple (the idea at least, the implementation can be quite complex). It is a program that grabs control of the display and input and serves client's requests. It uses DRM subsystem which locks the display to the first program that grabs it. That is why no other program can paint over the screen while the graphics system is running - all requests must go through it. The main responsibilities of a graphics system are:

- Input handling

- Window management

- Exposing an API and serving requests

- Drawing a mouse cursor

- Compositing (drawing the final image on the screen)

When an event arrives, it forwards it to the client, letting the client know that, for example, a mouse moved at x and y or a click happened. The client can then decide how to respond. In the old X11 days the clients had to make drawing requests. With Wayland and newer versions of X11, clients no longer make drawing commands. Instead they use a shared memory buffer and draw directly on it and simply ask the graphics system to show it on the screen. Wayland especially is much more secure than X11. It doesn't let other programs snoop around and better isolates clients from each other. It has to balance modern security expectations with usability, often making some power users frustrated. Wayland also combines the different components of a graphics system into one unified and integrated system. That's pretty much it. It's much simpler than people think. I even created a basic graphics system in JavaScript and HTML canvas and it took me no longer than 30 minutes to get a basic prototype working.

Unix Sockets

This year I also learned about kernel IPC mechanisms and Unix Sockets. Along the way, I had to also learn about virtual filesystems, since a socket file is itself a virtual file.

One of the core pillars of a kernel is IPC (Inter Process Communication). Programs often need to talk to each other, and that's where IPC mechanisms come in. There are many different IPC mechanisms, but Unix Sockets are one of the most versatile and widely used ones. DBus is built on top of Unix Sockets and X11 and Wayland use them to talk to their clients.

At the most basic level, Unix Sockets are just a buffer in kernel memory that two programs can read from and write to. A server program creates a socket file that listens for incoming connections. A client program connects to that socket file and starts sending and receiving data. At the kernel level, when two programs communicate over a Unix Socket, the kernel creates a buffer in memory. When one program writes data to the socket, the kernel copies that data into the buffer. When the other program reads from the socket, the kernel copies the data from the buffer to that program. This is where virtual filesystem comes in. A socket is a virtual file and Linux has special handlers for read and write system calls for this type of file. Instead of reading and writing data to and from an actual disk, the kernel invokes the virtual filesystem handlers. Another cool thing about Unix Sockets is that they are just a file and can be easily mounted in a Docker container, giving programs inside the container access to the socket and allowing them to run GUI programs.

And that's it! It all happens locally in the kernel. The kernel is the middleman that helps two programs communicate with each other.

A Unix Socket server and client can be written in just a few lines of C code:

// socket_server.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/un.h>

#define SOCKET_PATH "/home/tech-guy/spooky-socket"

int main() {

int server_socket = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_un server_address = {

.sun_family = AF_UNIX,

.sun_path = SOCKET_PATH

};

bind(server_socket, (struct sockaddr*)&server_address, sizeof(server_address));

listen(server_socket, 5);

for (;;) {

int client_socket = accept(server_socket, NULL, NULL);

char buffer[256];

int bytes = read(client_socket, buffer, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

buffer[bytes] = 0;

printf("Server got: %s\n", buffer);

write(client_socket, "Spooky reply! 👻\n", 18);

close(client_socket);

}

}

// socket_client.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/un.h>

#define SOCKET_PATH "/home/tech-guy/spooky-socket"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int client_socket = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_un server_address = {

.sun_family = AF_UNIX,

.sun_path = SOCKET_PATH

};

connect(client_socket, (struct sockaddr*)&server_address, sizeof(server_address));

char * message = argv[1];

write(client_socket, message, strlen(message));

char buffer[256];

int bytes = read(client_socket, buffer, sizeof(buffer)-1);

buffer[bytes] = 0;

printf("Client got: %s\n", buffer);

close(client_socket);

}

Linux Authentication and Users

One of the things that had always peaked my curiosity was how Linux authentication and users work under the hood. When you turn on the computer and it shows a login prompt, what exactly is it? What happens behind the scenes? And this one turned out to be quite a shocker. Are you ready for this? Linux does not actually have users or authentication mechanisms. No such exists in the kernel. Users, profiles, auth - all of that is in user-space.

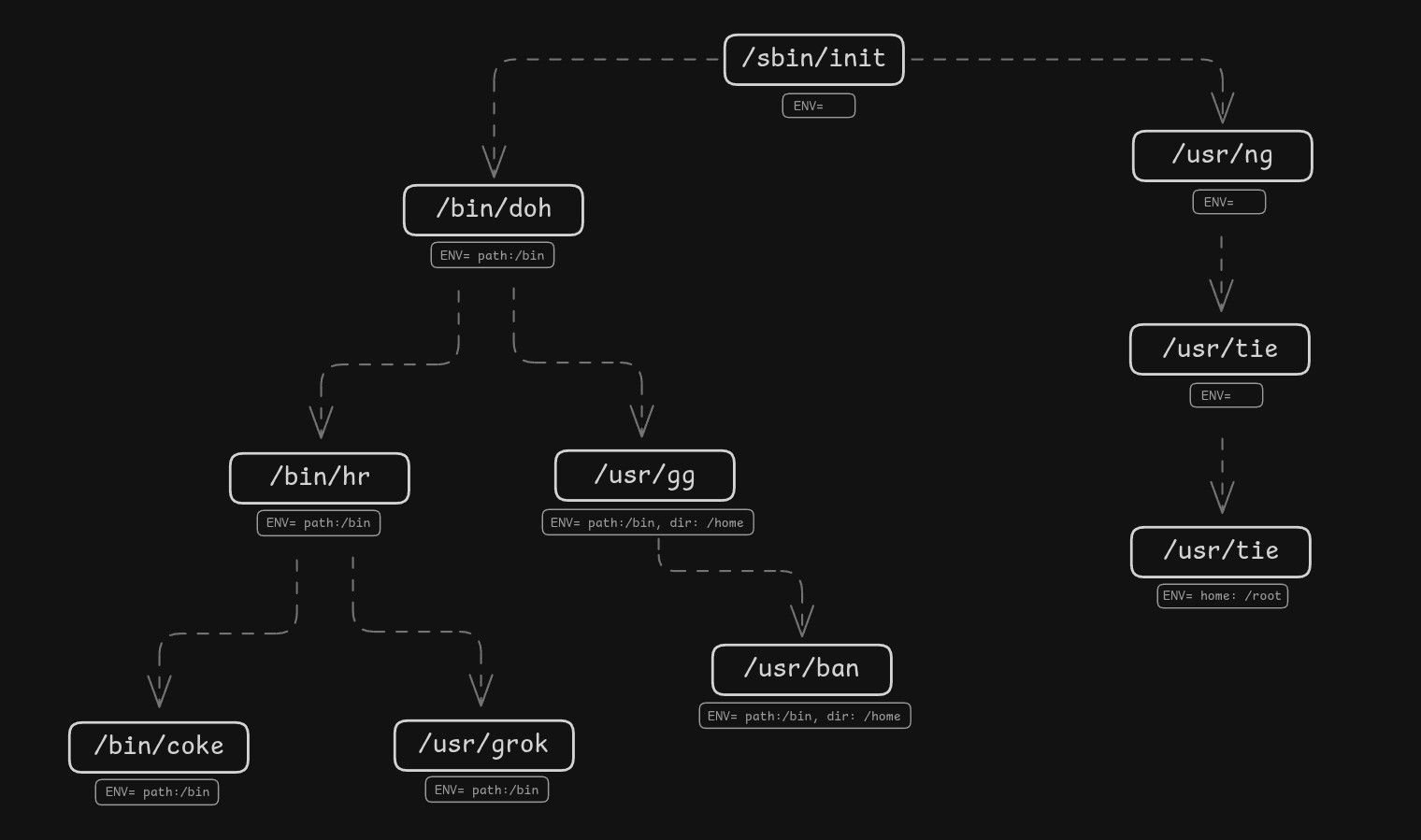

So then, what is that login prompt and how does it work? When you boot up a Linux system, the kernel starts the init process (/sbin/init). It does not know anything about users, usernames, passwords or authentication. You can boot Linux without requiring a login at all. Linux knows nothing about such thing.

Processes

What Linux does have is processes (task struct). And each process has a cred struct that has a UID (user ID) and GID (group ID) associated with it. Files also have UIDs and GIDs, along with permissions. The very first process (init) is started with root UID (0) and GID (0). When init starts other processes like bash or GNOME Shell, those processes often present a login prompt, and upon successful login, they change the UID and GID of the process to that of the logged-in user using the setuid and setgid system calls. From that point on, the process runs with the permissions of the logged-in user. All of this happens entirely in user-space.

Authentication itself is also a user-space mechanism. Programs like login, gdm, or sshd handle authentication by verifying the provided credentials against stored user data (like /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow). Usernames and passwords are purely a user-space concept. Kernel knows only about uid and gid numbers. It uses libraries like PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules) to perform the actual authentication checks. And again, all of this is a user-space convention. There is no rule that says you must use /etc/passwd or PAM. You can implement any authentication mechanism you want. This just happens to be the convention that most Linux distributions follow.

Sudo

Sudo is another interesting one. It allows a user to execute a command as root. When you run a command with sudo, it checks if you are allowed to run that command as root (based on the /etc/sudoers file). If allowed, sudo switches to root by taking advantage of the setuid bit. When an executable has that bit set, it runs with the permissions of the file’s owner (sudo being owned by root) instead of the user who launched it.

In desktop environments you might have noticed an Administrator toggle in settings. All it does is add or remove your user from the sudoers file. If your user is in the sudoers file, you can run sudo, it will ask for your password and then execute the command as root. On modern distributions, the sudo group is added to the sudoers file and users are added to the sudo group. If you want to give a user more granular permissions, you can edit the sudoers file and specify exactly which commands that user can run as root instead of giving them full root access.

Permissions

Permissions is the kernel mechanism that makes user-space concepts such as authentication actually work. Each process has a uid and gid (it actually has uid, euid, suid etc. but let's keep it simple). Each file also has an owner uid, gid and permissions (read, write, execute). When a process tries to do something with a file, the kernel performs a very simple check. First it asks - who are you? It checks the uid and gid of the running process. Then it looks at the file and its uid, gid and permissions to determine what the process is allowed to do with that file. For example, if the process has uid 40, guid 50 and the file has owner uid 40 and permission rw-r--r--, then the kernel will say - aha, so the file actually belongs to you, and according to its permissions, the owner can read and write the file - operation allowed.

Linux also supports ACLs (Access Control Lists) which provide a more fine-grained permission system. ACLs allow you to specify permissions for individual users and groups beyond the traditional owner/group/others model. ACL itself under the hood is implemented as extended attributes (xattr) on files. The kernel checks ACLs in addition to the standard permissions when determining access rights.

Remember, when the init process starts, it starts with root uid (0) and gid (0). It is the login manager that changes the uid and gid of the running process after successful login. When a process spawns a child process, that child process inherits the uid and gid of the parent. From that point on, the process runs with the permissions of the logged-in user. That's all that a login is - changing the uid and gid of the running process.

Environment Variables

Another topic I explored this year is environment variables. Everyone seems to use them and know what they are, but I wanted to understand what exactly they are and how they work under the hood. Are they a user-space concept? A kernel mechanism? Application feature?

Environment variables go all the way back to early Bell Labs Unix in the 1970s, created by Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson. In Unix, an environment is nothing more than an array of strings that gets passed to a process when it starts. The kernel stores these strings in the process’s memory (on the stack) and hands user-space a pointer array called envp when the program begins. From the kernel’s point of view, it’s just raw strings in memory. The kernel doesn’t interpret them, validate them, or enforce any format. That part is entirely left to user-space.

char *env[] = { "FOO=bar", "X=1", NULL };

execve("/usr/bin/node", argv, env);

The kernel tracks where the environment lives in the process address space using struct mm_struct (the memory descriptor). That struct has fields for the argument and environment regions.

struct mm_struct {

...

unsigned long start_stack; // Start of stack

unsigned long arg_start; // Start of command line args

unsigned long arg_end; // End of command line args

unsigned long env_start; // Start of environment variables

unsigned long env_end; // End of environment variables

...

};

When a process forks or spawns a child, the child receives a copy of the parent’s environment. After that, the two environments are independent: the child can change its own environment without touching the parent’s.

Environment variables are ultimately a kernel mechanism but managed by user-space programs. There is no special format that they must follow. You might have noticed that on most systems they look like KEY=VALUE pairs (e.g. DISPLAY=:0, PATH=/usr/bin). That is just a user-space convention. The kernel does not enforce that format. Programs can interpret and use these strings in any way they want.

Environment variables are normally inherited from parent → child unless overridden or cleared. A process can modify its own environment using libc functions like setenv, putenv, or unsetenv. Programs often store environment variables in config files like .bashrc, .env, etc. When the program starts, it reads those files and sets the environment variables using those libc functions.

The first process (/sbin/init) starts with an empty environment. It is up to init and other user-space programs to populate the environment as needed. One of the processes started by init is the cron daemon. You might have noticed that if you try to run a GUI program from a cron job, it fails. That's simply because the environment is very empty when cron is run. This can be easily adjusted by setting the necessary environment variables like DISPLAY, XAUTHORITY, DBUS_SESSION_BUS_ADDRESS, PATH in the cron job and then the GUI program will work just fine.

The History of Computing

This year I also took a deep dive into the history of computing. I learned that computers have been in development for as long as humans have existed. I learned about Charles Babbage, often called the "father of the computer", who designed the Analytical Engine in the 1830s. I learned about the early mechanical computing devices, electromechanical computers, and the transition to electronic computers in the 1940s. I learned about the computer revolution in the 1970s and 80s when computers became more accessible to the general public. It forced me to think about what a computer is fundamentally - at its core. A computer is anyone or anything that can follow instructions and process data. It doesn't have to be electronic. It doesn't necessarily need transistors. Electricity is just one medium. There have been computers literally made out of lego parts. The Analytical Engine used gears and leavers.

I also learned about early computer graphics systems and how they evolved over time.

You can read more about my exploration of a computer in this article: ➛ Read: What is a computer?

Ben Eater's 8-Bit Breadboard Computer

Speaking of what a computer is at it's core, this year I also re-watched the Ben Eater's 8-bit breadboard computer build (again). This time I got even more insight of how a computer works and what makes it tick. Last time I watched it was 5 years ago and it gave me a very solid understanding of what a computer is and how it works under the hood. This time around I focused more on understanding the clock and the control unit and filled some missing gaps in my understanding. If you haven't seen it yet, I highly recommend checking it out. It's a fantastic series that breaks down the inner workings of a computer in a very hands-on and practical way (literally building a computer from scratch on a breadboard).

➛ Watch: Ben Eater 8-bit Breadboard Computer

Microcontrollers

This year I also explored the embedded world. I learned that a microcontroller is a small, all-in-one computer just like any other computer. It has a CPU, RAM, motherboard and IO. Microcontrollers are small, cheap, low-powered computers, often with KHz or MHz CPUs and a few KBs or MBs of memory.

Most electronic devices have a microcontroller computer inside them these days. Some of them even have more powerful computers with a full-featured OS like the Raspberry Pi. It is becoming increasingly rare to find a device made out of discrete parts since microcontrollers have become very cheap and affordable. Think of your car, washing machine, dishwasher, refrigerator, microwave, smart lights, smart plugs, alarm system, AC - all of them have computers inside. There are possibly hundreds of computers running in your house right now.

Timezones

This year I also learned about timezones and how they work. Little did I know that it would turn into such a rabbit hole. I learned about UTC, GMT, timezone names, offsets, daylight saving time, atomic clocks, IANA timezone strings etc.

I learned about UTC and how it doesn’t belong to any specific place on earth. Even though the idea originally used the Greenwich meridian (0° longitude), that doesn’t mean Greenwich always shows the same time as UTC on a clock. You can have 12:00 UTC at 0° longitude, but the local civil time in that same spot might be 13:00 or 14:00, depending on what time-zone laws the region follows.

I learned about how to properly store time. UTC should be used for past events. For historical data UTC is best because it's unambiguous and consistent. For future events, UTC alone is not enough – when scheduling future times (like appointments), you need to preserve the user's original local time and timezone, because daylight saving time and timezone rules can change.

Timezones are a complicated mess. China, for example has only one timezone for the entire country, even though geographically it spans a huge area. People in easter and western parts of China even use two clocks - one for official time and another for local time. Some countries have half-hour or even 15-minute offsets. Daylight saving time rules change frequently, and some regions adopt or abolish it altogether. There are even places on earth with a different timezone in the middle of a country. Timezones are messy, political and inconsistent.

When displaying time to users, it is always important to show the offset along with the time. Simply showing "3:00 PM" is not enough. You need to show "3:00 PM PST (UTC-8)" to avoid confusion. The only technically precise way to represent a time is to use the IANA timezone because it captures all the historical and future changes to timezone rules (e.g. Germany/Berlin, America/New_York).

To get a feel for how painful timezones can be, you can watch this video: ➛ Watch: The Problem with Time & Timezones - Computerphile

Event-driven Programming

This year I also explored event-driven programming and the importance of it. Events are often used to decouple logic and keep a system modular. It is also very important to be able to trace and debug events as they happen.

Events allow for a very modular architecture. Your system emits events at different points in time and this allows you to create a completely independent and pluggable module which hooks into these events without needing to make any changes to the core part of your system. For example, you might create a Notification module which listens to various events in your system and sends e-mail, text messages, push notifications and performs other actions related to notifying your users. All of this without ever needing to change any part of your existing codebase. Your module can have a single responsibility, be completely self-contained and independent.

For example, POS systems often have a local law requiring them to implement the payment system as a completely separate module. Without events and hooks this becomes impossible. You look at the code and see that everything depends on everything, the payment system is intermingled with every other part of the system. You throw your arms up in the air and say, no way, this can't be done. Payments are the very core of a POS system. It runs through everything. But that is just a sign of a badly architected system. It doesn't need to be this way. Everything should not depend on everything. That's a brittle system. With an event-driven, modular architecture you simply emit events and let the payment module hook into these events and handle the logic.

Think of a radio broadcast (emitting events). The broadcaster simply broadcasts into the air. Anyone who wants to and has a radio (listener) tuned to the frequency hears the message. The broadcaster doesn’t know or care who’s listening.

I explored things like DBus, inotify, Nuxt hookable system, Pub-Sub pattern etc. Events are everywhere in programming. Big and serious systems rely on events to keep things modular and decoupled.

JSON Web Token (JWT)

I also learned about JSON Web Tokens (JWT) and how they work. Specifically focusing on security and encryption. JWT is a simple piece of data consisting of 3 main parts: header, payload and signature. They are stateless - meaning they can be verified without needing a database lookup.

A server generates a JWT token by creating a header and payload and making a signature using a secret key. It sends this token to the client and the client sends it back with every request. The server verifies it by generating the signature again using its secret key. If they match and the token is not expired, the server knows it is valid and grants access.

As far as the header and payload goes, they can contain pretty much any json data you want to store there. There are some standard payload fields like exp, iat etc. and header usually includes fields like alg and type.

JWT is as secure as the encryption algorithm used and the strength of the secret key. If you use any modern encryption algorithm and a strong key, it is considered to be as safe any any well encrypted data. No one yet has broken modern encryption algorithms.

Server-Sent Events (SSE)

This year I explored the idea of using SSE for server-client communication. I learned about how SSE works, its strengths and weaknesses and weather or not it is a good replacement for WebSockets.

Even though SSE is often advertised as a simpler mechanism compared to WebSockets, in my experience I found too many issues for it to be considered a viable option.

- Proxies often drop connections unless you manually implement a ping mechanism

- Safari does not reconnect when connection gets lost. You need to implement your own ping based reconnection mechanism.

- You need to manage connections which can get very complex. WebSockets on the other hand only have one connection.

- Lacks good tooling and ecosystem is weak compared to WebSockets.

- No support for authentication, need to use 3rd party libs for that since the built-in EventSource doesn't even support sending headers.

- SSE has 6 connection max limit. This is a pain in local development where you might have more than 6 tabs opened and don't understand why your SSE is not connecting.

Socket.io and Websockets

WebSockets with Socket.io solves a lot of these pain points. It has great tooling (Socket.IO Admin UI), multiple fallback and reconnection mechanisms. It has auth built-in, it doesn't require juggling connections, has no connection limit and is fully bi-directional.

If you want to save yourself a lot of pain - use Socket.IO, you won't regret it. This year I also created a nice, Vue 3 useWebsocket composable built on top of socket.io.

Looking back at 2025, this year was about pulling back the curtain on how computers really work—from the very basics of what a computer is, to the intricacies of the kernel and the graphics stack, IPC mechanisms, users, permissions, and authentication. Here's to another year of learning and discovery!