You are thinking about Docker the wrong way

Most people are taught that a Docker container is like a lightweight Virtual Machine that shares the host's kernel. You run programs inside this container similar to how you run programs on a VM. I'm here to tell you that nothing could be further from the truth.

Docker Container is not a lightweight VM

A Docker container is not a lightweight VM. There is no such thing as a container and you do not run your programs inside it. That's juts bad marketing language. What most people think of as a "container" is actually just a running program which has been namespaced. It is a program just like any other program running on your computer. In fact, if you take a look at the process list on your computer, you will not find a "container" process anywhere. Instead, you will find the actual program that is running. The only tell-tale sign of it being a "container" is the fact that it has been forked by a parent "containerd-shim-runc" process.

$ ps auxf

containerd-shim-runc-v2

└── node app.js

What is a Docker Container?

Like we established above, there really is no such thing as a "container". It is a namespaced process running on your computer like any other. But I said namespaced. So, there is something special about it after all? Yes, there is. It's time to learn about namespaces and cgroups.

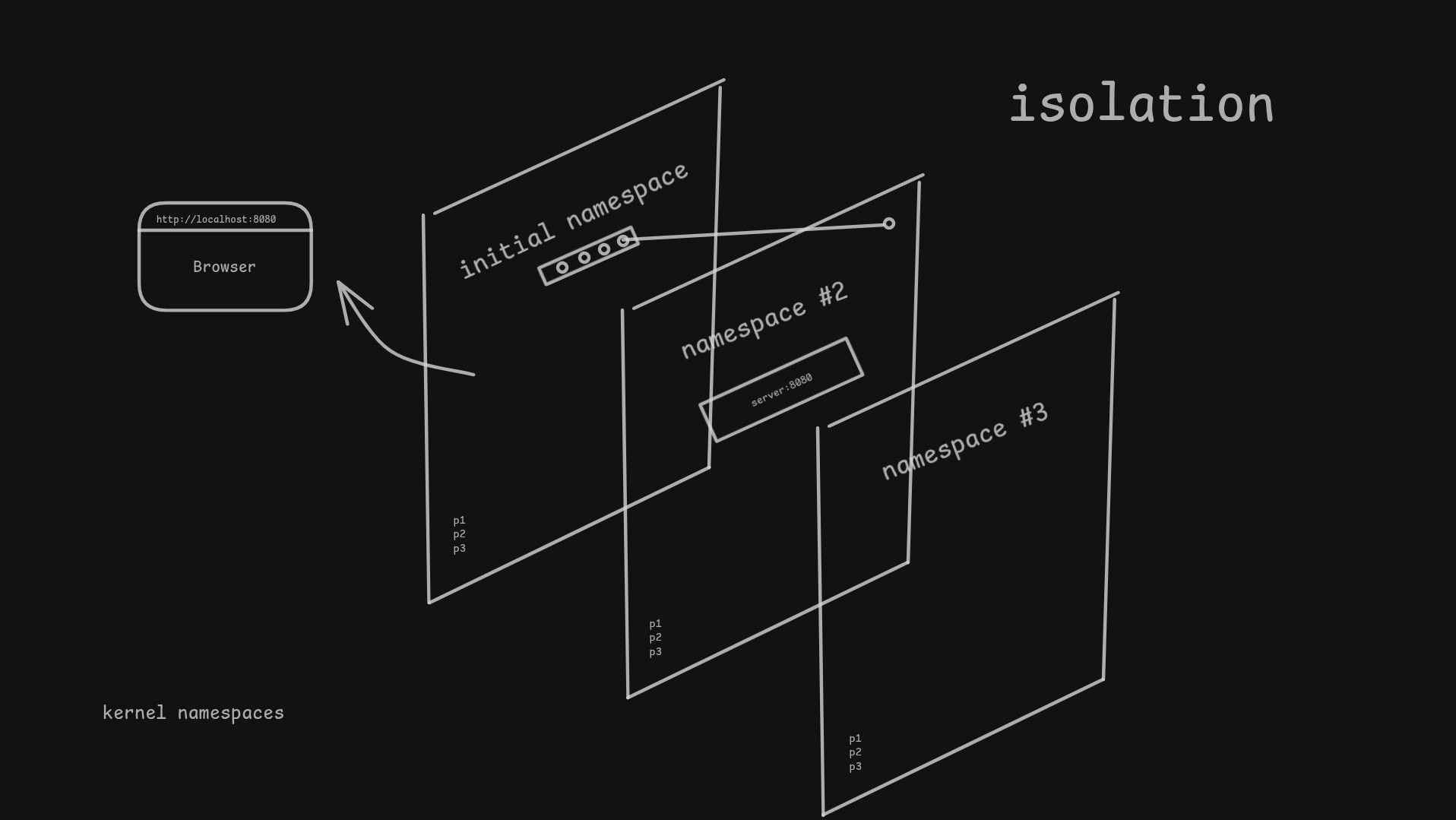

Namespaces

Back when Unix was first created, it was designed with a global view of the system in mind. There was one process list, one file system, one network stack, and so on. But as time went on, users wanted to be able to isolate processes from each other. For example, you cannot bind two processes to the same port. You cannot easily test software in isolation. You cannot install multiple versions of the same program without them conflicting with each other. People realized they needed a way to isolate processes from each other. This is where namespaces come in.

Namespaces are sort of like grouping processes and putting them in their own little boxes. This is not a perfect analogy, as I said earlier there is no such thing as a container, and you do not run a program inside one. Namespaces are more about giving processes a different view of the system. Perhaps a few lines of code will help illustrate this better.

Consider a system without namespaces:

let processes = ['init', 'systemd', 'node']

let hostname = 'ucla-mainframe'

function spawn(name) {

processes.push(name)

}

function ps() {

return processes

}

function setHostname(name) {

hostname = name

}

function getHostname() {

return hostname

}

spawn('bash')

spawn('nginx')

As you can see, we have a global process list and a global hostname. Any process can see all other processes and the hostname is the same for everyone.

Now consider what a namespaced system would look like:

function createNamespace(hostname, fs) {

return {

hostname,

processes: ['init'],

fs

}

}

function spawn(name, ns) {

ns.processes.push(name)

return { name, ns }

}

function ps(proc) {

return proc.ns.processes

}

function hostname(proc) {

return proc.ns.hostname

}

function setHostname(proc, name) {

proc.ns.hostname = name

}

function readFile(proc, path) {

return proc.ns.fs[path]

}

// host namespace

const hostFs = {

'/home/jimmy/hello.txt': 'hello from host'

}

const hostNs = createNamespace('host', hostFs)

const bash = spawn('bash', hostNs)

readFile(bash, '/home/jimmy/hello.txt')

const containerFs = {

'/home/jimmy/hello.txt': 'hello from container'

}

const containerNs = createNamespace(hostNs.hostname, containerFs)

const sh = spawn('sh', containerNs)

setHostname(sh, 'container')

readFile(sh, '/home/jimmy/hello.txt')

readFile(bash, '/home/jimmy/hello.txt')

In this example, we have created a simple namespacing system. Each namespace has its own process list, hostname, and file system. When we spawn a new process, we pass in the namespace it belongs to. When we read a file or get the hostname, we do so in the context of the process's namespace. Each process has its own process list, file system, network stack, and so on.

Lets now recreate in a few commands what Docker does under the hood when creating and running a container.

# Create a new namespace for a program (stop sharing with the host)

unshare --fork --pid --mount --uts --ipc --net --mount-proc bash

# Create a new root filesystem

mount --make-rprivate /

mkdir ~/newroot/{bin,etc,lib,home,oldroot}

cp /bin/busybox ~/newroot/bin/

mount --bind ~/newroot ~/newroot

pivot_root . ~/newroot/oldroot

cd /

mount -t proc proc /proc

umount -l /oldroot

# Now run your program (this is your "container")

/bin/busybox sh

Cgroups

Namespaces are great for isolating processes, but they do not provide any resource management. This is where cgroups come in. Cgroups, or control groups, are a Linux kernel feature that allows you to limit and prioritize resources for a group of processes. With cgroups, you can limit the amount of CPU, memory, disk I/O, and network bandwidth that a group of processes can use.

When you run a Docker container, Docker creates a new cgroup for the container's processes. This cgroup is used to limit the resources that the container can use. For example, you can limit the amount of memory that a container can use by specifying the --memory flag when you run the container.

Who uses containers?

I mean namespaces and cgroups. A lot of things. Docker, Flatpak, Kubernetes, systemd, LXC. Namespaces and cgroups have become fundamental. They are everywhere. And once you understand how they work, everything else makes will start to make a lot more sense.